Availability of resources determine the cost of production, and endowments in turn determine the availability of resources. This naturally leads people to prioritize outputs that use the most available inputs for outputs of equal value, explaining why businesses of countries endowed with high-value commodities tend to prioritize the extraction and sale of these resources compared to countries that do not have such commodities. Not only are the outputs of these businesses high value, they are also readily available.

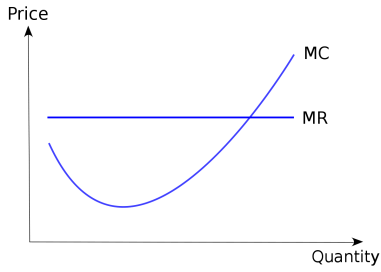

This also explains why countries without high-values commodities prioritize outputs that require human capital. At the level of comfortable sustenance, wages are cheap, and the economic ascent of Asian tigers, such as South Korea and Japan, follow this principle. Both countries grew on the back of companies finding success in labor-intensive industries such as textiles, manufacturing, shipping, and chemicals. These businesses could ramp up production as wages, paid in local currency, constituted a majority of the marginal cost and did not exceed marginal revenue as output increased.

Examples go beyond businesses and extend to governments. Government-led exports of human capital have many precedents. South Korean laborers were sent to Germany in exchange for German Mark-denominated loans that provided funds. How these funds advanced South Korea’s strategic industries exceeded the costs of the export from the leadership’s point of view.

Focusing on labor-intensive industries in countries without high-value commodities also presents lasting advantages supported by two economic principles, Balassa-Samuelson Effect and the Dutch Disease. The former tells us that productivity increases in any sector in a country can lead to wage inflation (i.e. shoe shiner being able to charge more as his/her clients get wealthier), while the latter tells us that demand for high-value commodities equates to demand for that country’s currencies, inflating all costs. While all countries are subject to the Balassa-Samuelson effect, countries without high-value commodities do not have to solve for the Dutch Disease.

This presents an opportunity to investors. In markets that are not endowed with high-value commodities, it can pay to back labor-intensive industries. This can especially be the case if the revenue is denominated in hard currency through exports.

Unfortunately, marginal costs of many labor-intensive industries such as manufacturing require include inputs outside wages such as electricity and logistics, posing risks linked to governments that are outside outside the investors’ sphere of control. Nonetheless, successful precedents are plenty, both at the level of businesses and nations. It is hard to overlook this sub-set of opportunities.